Every time we hear about a tragic car crash, the story is usually framed around individual blame. Someone made a mistake, someone wasn’t paying attention, or someone was reckless. But beneath these headlines lies a harder truth. Our urban design itself creates the conditions for these deaths. Poor urban planning is not just an inconvenience or an aesthetic misstep. It is a public health crisis that costs lives every day.

In too many American cities, Charlotte included, roads are engineered like highways. They are wide, fast, and hostile to anything but cars. Corridors such as Independence Boulevard prioritize vehicle flow over human life, encouraging high speeds and leaving pedestrians and cyclists exposed. In this environment, even a brief lapse of focus, just a few seconds, can turn a mistake into a tragedy.

Just a few hours ago, as I write this post, there was an accident on Independence Boulevard that sent six people to the hospital, one with severe life-threatening injuries. It is tempting to place all of the blame on a driver going too fast. The harder truth is that the driver was simply responding to incentives created by reckless city planning, such as wide lanes, high speed limits, and a lack of safe transit alternatives. If the road had been designed to slow speeds and protect people, it is likely this crash would not have been so devastating or have happened at all.

And incidents like this are far from rare. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department website listed seven similar traffic events in just the past three hours alone.

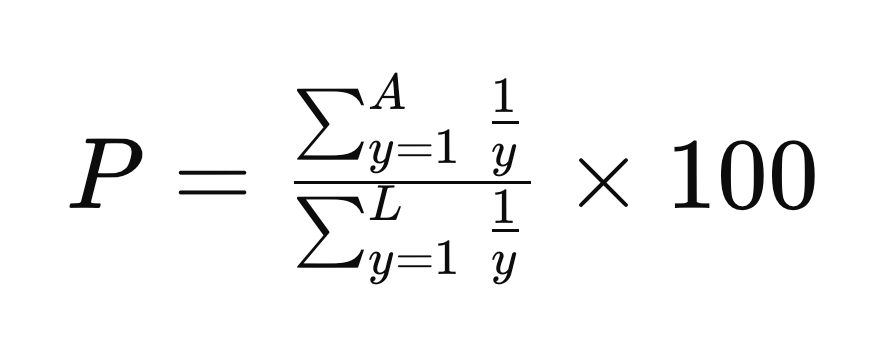

To err is human. Every driver will make mistakes behind the wheel, such as misjudging a turn, glancing at a phone, or reacting a second too late. A safe transportation system recognizes this reality and builds in forgiveness. Narrower lanes, slower speeds, and protective infrastructure can ensure that a mistake does not automatically mean death. But our current design does the opposite. It demands flawless driving from every user, every second. That is not just unrealistic. It is negligent.

There is another layer to the problem. Many people simply should not be behind the wheel of heavy machinery. Teenagers, seniors, those with medical conditions, or people who are poor drivers are still forced to drive because cities have left them with no alternatives. By designing systems where car travel is the only viable option, we compel people into dangerous situations that put their lives and the lives of others at risk.

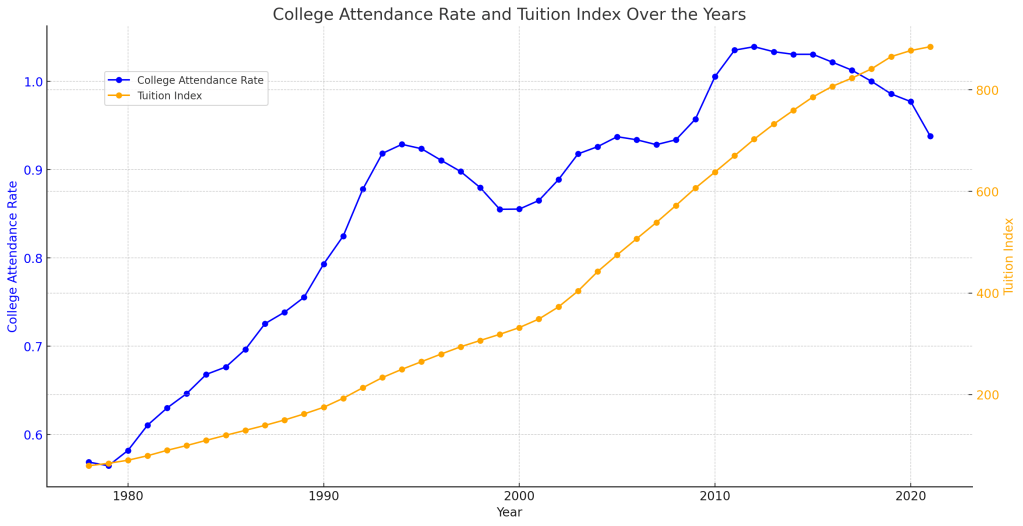

The spread-out, car-dependent development pattern of low-density housing, long commutes, and seas of parking creates endless demand for driving at higher speeds. Strong Towns and other urbanist voices have long warned that this model is both financially unsustainable and physically dangerous. More driving leads to more crashes, and higher speeds lead to more fatalities. The math is simple, and it is killing us.

If we want fewer deaths, we must stop pretending this is about individual failure. Real safety comes from systemic change.

- Slower streets with narrower lanes, traffic calming, and enforced lower speed limits.

- Safe alternatives such as protected bike lanes, sidewalks, and reliable public transit.

- Walkable, mixed-use communities where housing and jobs are close together, reducing the need to drive.

- Equitable design that prioritizes vulnerable road users and invests in underserved communities.

We call crashes “accidents” as if they were unavoidable acts of fate. They are not. They are predictable outcomes of policy choices, zoning codes, and street designs. Every fatal crash reflects a system that refuses to put people’s lives above the convenience of cars.

Poor urban planning kills. With better choices and people-first design, we can build cities where human mistakes no longer cost human lives.